Sense and Sensibility: the art of adaptation

In which the Dashwoods do Devonshire and we consider various ways to tell the same story

A second book completed in this year of reading Jane Austen.

A third of the way through this glorious adventure.

Welcome to all things Sense and Sensibility.

Sense and Sensibility seems to hold a very interesting place in the Austen canon. It appears to be one of the lesser read (and dare I say perhaps lesser loved?) of her novels, but is undoubtedly one of the most famed and loved of the screen adaptations—I’m of course referring to the 1995 film, written by Emma Thompson and directed by Ang Lee.

Certainly for me with Sense and Sensibility, over time my brain has come to consider Emma Thompson’s version of events as ‘the story’. This of course makes reading the book again such a gift, as so much comes up that I’ve forgotten happens at all or originally happens in a different way.

Considering Sense and Sensibility in book, film and TV form provides us with an excellent opportunity to dive a little deeper into what makes a good adaptation—the choices made in the tone of the storytelling and in the portrayal of characters lead to a shift in the telling of the story and perhaps even in the story that is being told.

So tie up your bonnet strings, be careful coming down the hill and let’s go!

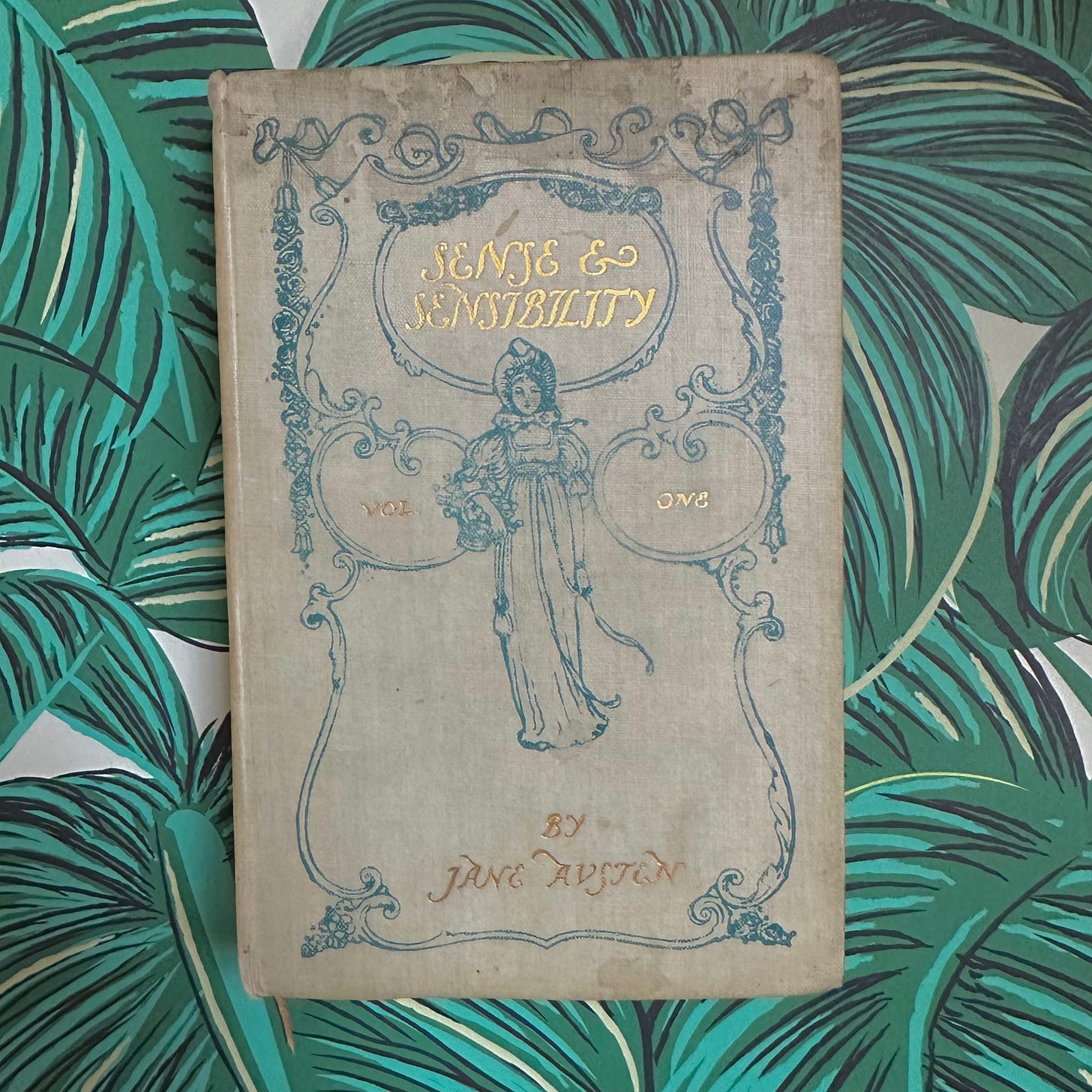

Actually, before we dive into the story itself, let’s first take a moment to admire this thing of beauty:

This is a 1901 edition of volume one of Sense and Sensibility.

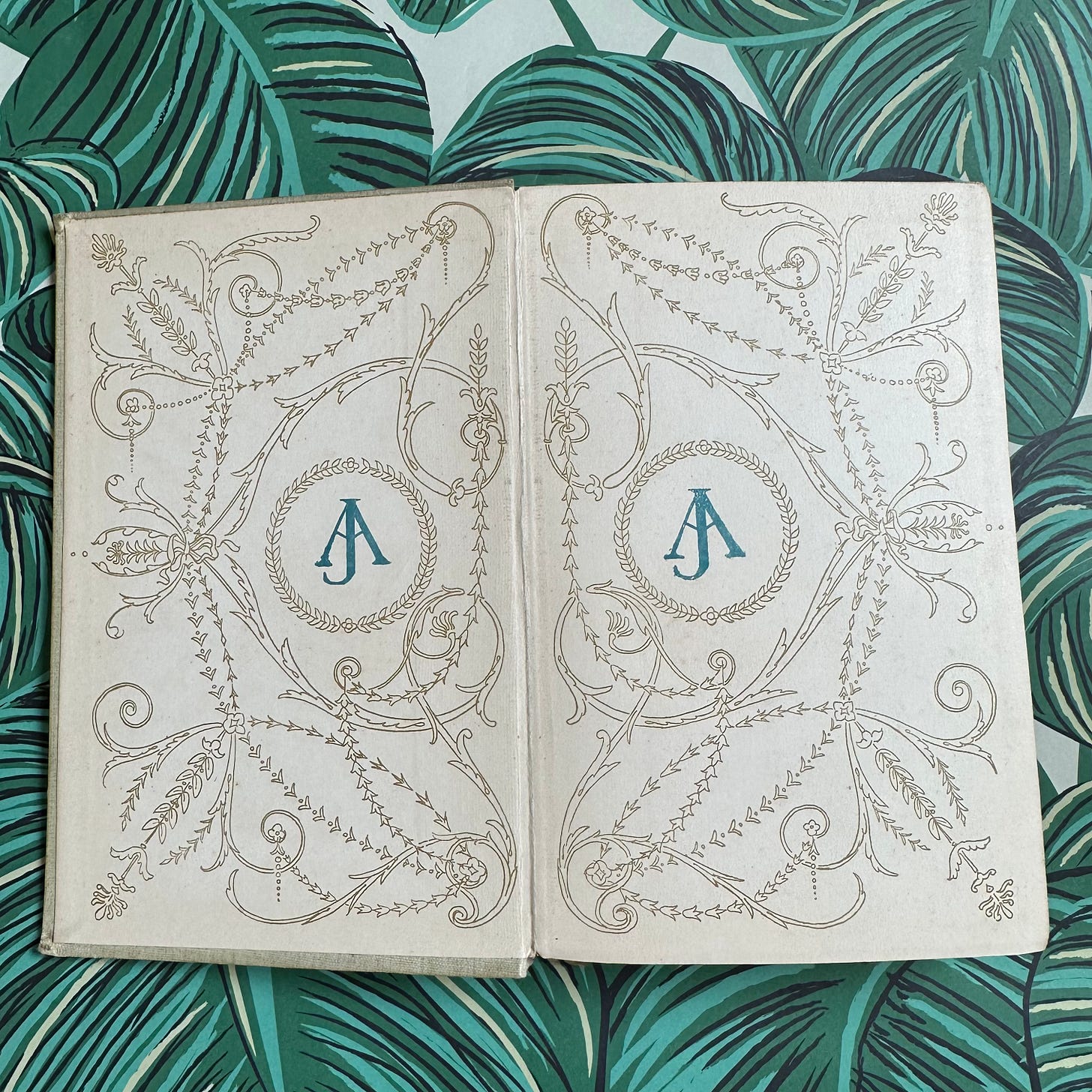

It has cut pages and stunning endpapers.

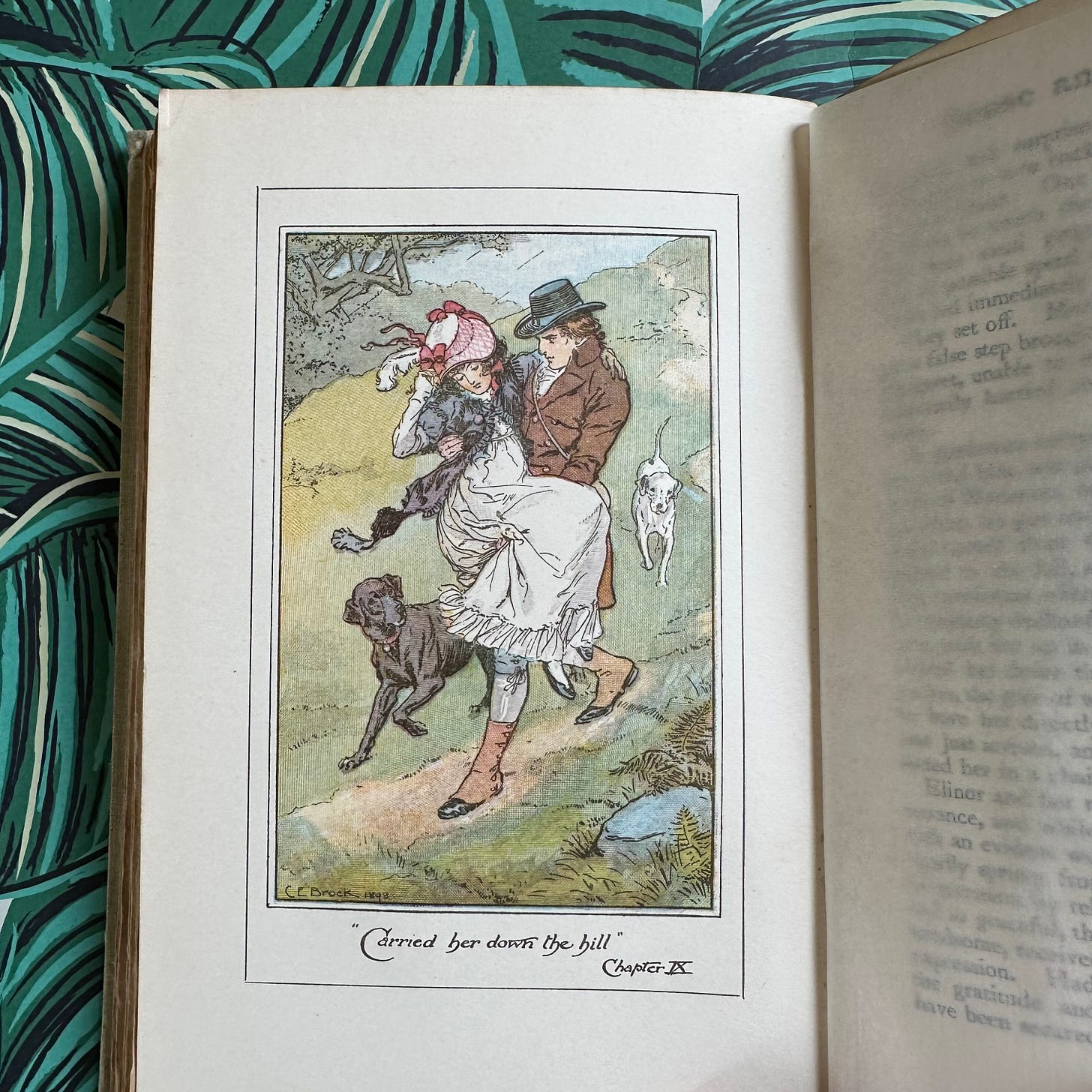

And beautiful coloured illustrations (by CE Brock).

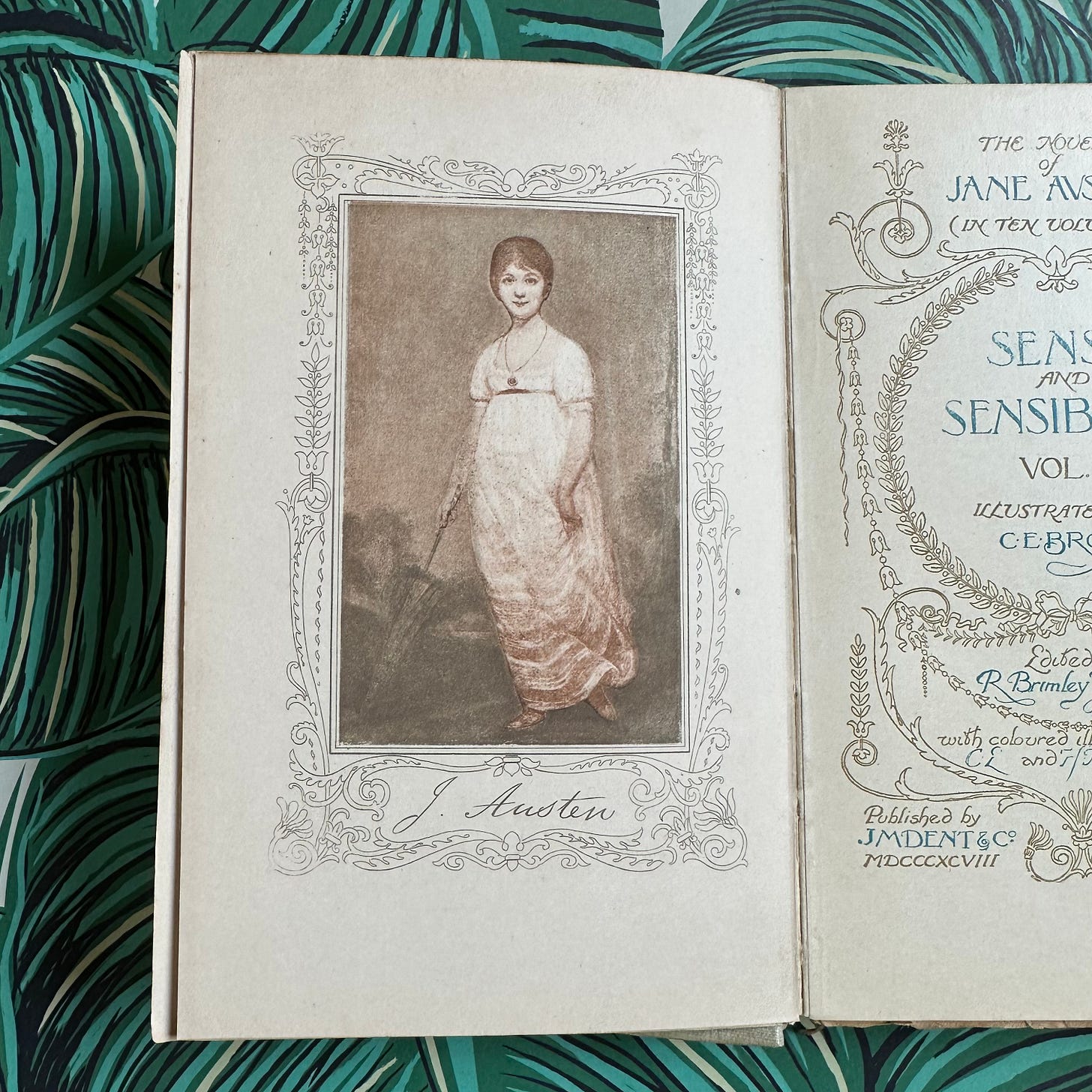

There is even a portrait of Jane Austen in the frontispiece.

This is from a portrait of Jane Austen, said to have been painted when she was on a visit to Bath, at about the age of fifteen, by Johann Zoffany. The original is in the possession of the Rev. J. Morland Rice, Rector of Bramber, Sussex, and grandson of Miss Austen’s second brother, Edward. It is here reproduced by the kind permission of Mr. Rice, who tells me that it formerly belonged to Colonel Austen of Kiplington, a descendant of the kind “Uncle Francis” Austen, who was Miss Austen’s great-uncle, and the early friend of her father. He gave it to his friend, Mrs. Hardinge-Newman, a devoted admirer of the novelist, and her step-son, Dr. Hardinge-Newman, left it to Mr. Rice—Ed. (Text taken from List of Illustrations)

I’m incredibly grateful to the kind friend who found this at a charity shop and sent it my way. Now everyone keep an eye out for volumes two and three!

As with Northanger Abbey, before we started the readalong I would have considered Sense and Sensibility as falling ‘somewhere lower down’ in my Austen novel rankings. And just as with Northanger Abbey, close reading day by day and week by week swiftly evaporated any sense of ‘better or worse than’ and left me simply relishing the opportunity to steep myself in Austen’s words and world.

We have two heroines (not alike in temperament) in fair Devon, and as much as my shared sensible older sister sentiments want me to claim main character status for the incredible Elinor, I do subscribe to the yin and yang notion—that Marianne and her wild romantic feelings are needed to make Elinor a more interesting proposition. These two undoubtedly come as a pair.

Austen’s portrait of sisterhood in this novel is wonderful. It is perhaps the most realistically drawn example from her novels. for while Lizzy and Jane Bennet are incredibly loving and close, Jane is so soft and easygoing that Lizzy never needs to call forth her trademark sass.

The relationship between the Dashwood sisters, on the other hand, is tested repeatedly and never found wanting. This seems very healthy. Much of the dialogue-based humour in the book comes in the form of Elinor’s drily witty retorts, most of which are sent in Marianne’s direction. Elinor and Marianne can disagree, even heatedly at times, about their different approaches to life. They frustrate each other enormously and don’t try and hide it. But they are never not united and supporting each other. All is underpinned by their bond and their love. By the end of the novel, Marianne’s learning about life (all hail the Austen heroine’s journey of self-discovery) has brought her closer to appreciating and understanding her sister than ever.

While money and class are recurring themes in Austen’s work, Sense and Sensibility shows us the biggest negative shift in circumstances that characters have to contend with. And they are women, who can do nothing about it. Women ‘marrying up’ and men being advised against or temporarily prevented from ‘marrying down’ is standard Austen fare (notwithstanding lucky old Emma Woodhouse), and while that is an issue in the romantic plots in Sense and Sensibility, the bigger ‘money story’ at play here is the dire situation that the Dashwoods find themselves in and realising how utterly their lives were upended in a matter of months.

The men of Sense and Sensibility form perhaps the one element of the novel that indicates Austen was still very early in her writing career here. The characters of Edward, Willoughby and Colonel Brandon are all pretty thinly drawn (Edward the diffident and questionably deserving, Willoughby the charming, selfish cad, and Brandon the bland ‘un, but best of a bad bunch) and much of the actual romancing unsatisfyingly happens off page—something both film and TV adaptations look to address.

If you haven’t read Sense and Sensibility, or haven’t read it for a long time, and if like me you knowingly or unknowingly use the Emma Thompson film as your frame of reference for the storyline, please give the book a read. Revel in Austen’s truly remarkable ability to create—and then just as ably eviscerate—a character in a matter of paragraphs (watch out John and Fanny Dashwood, the Steele sisters, Robert Ferrars!), or equally show us that people are layered and not so easily pigeonholed as first judgements would allow (looking at you Mrs Jennings and Mr Palmer). Take note of the double-underlined life lesson that men without occupation are likely to end up in a sticky situation of some kind. And most of all enjoy the beautiful portrait of sisters, in fact of a family of women, who support each other unwaveringly and are eventually rewarded with their happily-ever-afters.

For further in-depth analysis of the book, I refer you as ever to the excellent Substacks of

and .Top book moments that I’d forgotten all about since last reading:

NB: this list is truly spoilertastic!

There is a mini Elinor and Colonel Brandon match-up mix-up. I’m not altogether against this pairing actually, both have good sense and compassion—I feel Elinor would appreciate rather than upbraid a man for his use of a flannel waistcoat. But alas, not to be. The scene where we witness Mrs Jennings misinterpret a conversation between the two seems almost Shakespearean in its mischievous confusion. I’m also not altogether against Edward having a moment’s pause where even he thinks Elinor may have shifted her affections to someone less secretly taken.

Willoughby returns near the end of the book to drunkenly request forgiveness. I’d completely forgotten about this and Austen drops his unexpected Cleveland arrival at a chapter end in true cliffhanger style—I may have actually gasped. While as I’ve mentioned book Willoughby is relatively thinly drawn, from what we are given I do think Austen never built him up for us to fall for him as Marianne does. He was always too good to be true. And while he gets the opportunity here to plead his case to Elinor, we don’t forgive, we believe Marianne to be better off without him, but we soften towards him, a little. And we know that’s ok because Elinor does too.

Everything is a touch more pragmatic under Austen’s pen, and while book Marianne’s near death experience at the Palmers’ country pile did indeed come after indulging in some precious “invaluable misery” and “tears of agony” while fancying she could see Willoughby’s home turf, Combe Magna, in the distance, the actual catalyst of her illness is more likely “sitting too long in wet shoes and stockings”—no dramatic moony faint in the rain here.

Lucy Steele has a sister! And she’s hilarious and won’t stop saying the word ‘beaux’. (Daisy Haggard’s portrayal of Anne Steele is one of the best things about the BBC Sense and Sensibility adaptation, more on which much further below).

In 2020, when my then six-year-old daughter and I were safely ensconced at home reading our way through the six Austen novels, she approached me one day with a serious face and a seriously bemusing question:

What does ‘soaking someone’s chays’ mean?

After seeking a little further context, I discovered this was a Sense and Sensibility-related query and referred to Willoughby politely refusing Mrs Dashwood's entreaty to sit down after he’d rescued Marianne in the rain!

So before we head into discussion of the screen adaptations, consider this my regular reminder to those with middle grade reading age children or grandchildren ripe for conversion to the cult of Austen, that the Awesomely Austen series is absolutely wonderful—and will doubtless invoke a whole heap of interesting and amusing questions and conversations.

The moment the last word was read and the book closed, off I went to put on my bonnet and rewatch the 1995 film adaptation of Sense and Sensibility.

As I mentioned in my 2025 anniversaries newsletter, the beautiful, Ang Lee directed film is now an unbelievable 30 years old. It was one of four Austen adaptations/retellings to have emerged in 1995, all of which went on to be long remembered and much loved.

This adaptation had in fact been in the works for years. Producer Lindsay Doran worked with Emma Thompson on Dead Again (remember that?!), and after various conversations fangirling over Austen, decided Thompson would be the ideal person to adapt her favourite novel for the screen. Thompson had never written a film script before and spent years working on it in between acting jobs. Finally, in the mid 90s when British actors were definitely having a moment and heritage filmmaking was about to have another, the project came together.

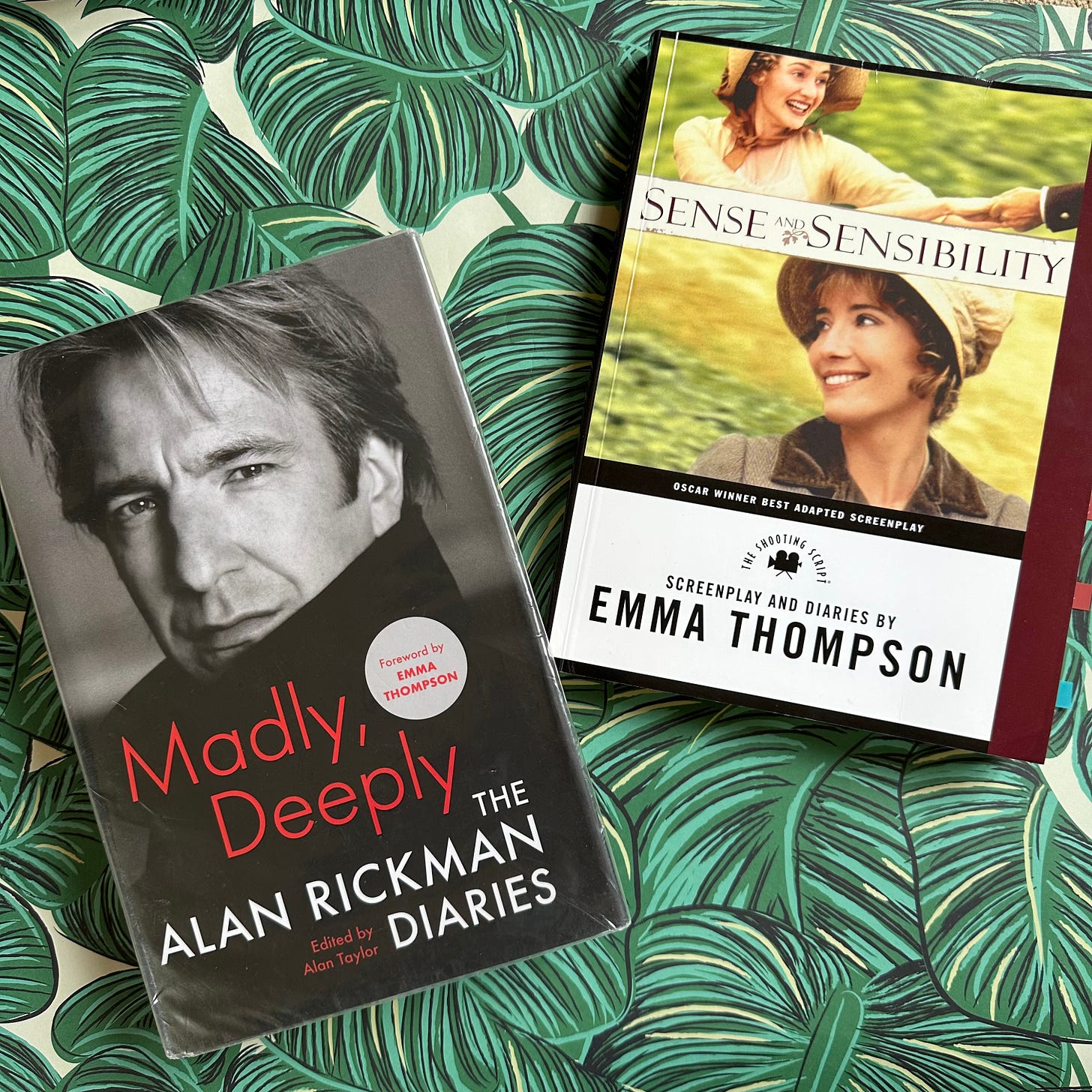

Thompson talking about the adaptation process itself is absolutely fascinating, and we’re lucky to have her Screenplay and Diaries to offer an incredible window into the whole experience (I also got hold of a copy of Madly, Deeply: The Alan Rickman Diaries to compare notes on filming). Creating a much-loved film and winning an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay on your first attempt is definitely not to be sneezed at.

Thompson also won the Golden Globe for her screenplay and the speech she gave is surely one of the finest and funniest—and proof perfect she was the right woman for the job:

Emma Thompson’s watchwords for the screenplay were romantic and funny. And perhaps it’s the amplification of both these elements of Austen’s original that created a result with broader appeal than a straight adaptation (this lighter tone is definitely a counterpoint to the later BBC adaptation) and, along with the beautiful cinematography and exceptional cast, encapsulated a warmth that has doubtless aided its longevity.

This ‘making of’ film with the cast and crew is absolutely wonderful—it shares so many fascinating behind-the-scenes insights, and all involved talk about how funny and romantic the adaptation is:

Interestingly, Paula Byrne in her excellent book, The Genius of Jane Austen: Her Love of Theatre and Why She is a Hit in Hollywood, suggests Austen would be appalled by the emphasis the film places on the romantic aspect of the story:

Though the performances in Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility were outstanding, the film’s insistence on a highly idealistic presentation of romantic love ultimately promulgates and vindicates precisely the values that the novel satirises.

I’m not sure I totally agree.

As both a lover of Austen and a successful Hollywood actress, Thompson had a pretty singular understanding of the brief and sympathetically dramatised the work to tell the story in a fresher way while thoughtfully retaining the essence of what makes Austen Austen. As Sam West points out in this fascinating Jane Austen House lecture on Austen adaptations (which I’ve mentioned before and is well worth a watch), great screen adaptations bring new readers to the novels. The more loved the film, the more readers can enjoy this rabbit hole journey of comparing and contrasting to its source material.

The ‘presentation of romantic love’ in the film is certainly amplified from the novel, but as discussed above this is perhaps the area of the storytelling that genuinely benefits from more focus than originally given. In the book we barely witness any interactions between Edward and Elinor at Norland, but on screen we wouldn’t be at all invested in what gets in the way of their love if we didn’t see it develop in the first place. All the male characters needed to be built up into more believable lovers for us to care about their interactions with and intentions towards our beloved heroines.

The casting of the three ‘heroes’ is immaculate (as it is throughout). The first time Edward Ferrars is described as ‘diffident’ in those early chapters at Norland Park, you know exactly why ‘fresh from Four Weddings’ Hugh Grant was top of Thompson’s list. Book Edward is pretty dull truth be told and between Thompson’s script and Grant’s acting a whole new lease of life was given to this love story. The warmth Edward shows towards Elinor’s youngest sister Margaret at Norland in the film cleverly rounds out both those characters in one fell swoop from their quieter book iterations.

Willoughby is perhaps the character who receives the biggest shift in presentation between novel and film (and even more so in the later TV adaptation). Book Willoughby is the most neutral version, and as I mentioned above, I think we’re supposed to see him more clearly than Marianne does. Film Willoughby, on the other hand, is written to sweep us all off our feet. Dramatically this means we can be as shocked and disappointed as Marianne that his past is seriously flawed and his future predicated on a preference for wealth over love. Thompson doesn’t include the Cleveland scene where he pleads his case as this would muddy our thoughts about him, and more crucially from the film’s storytelling perspective, would interrupt the building energy of the Marianne/Brandon romance.

Film Willoughby encapsulates the heartbreaking romance that just wasn’t meant to be. Closing the film with him in full ‘hero mode’ on a white horse watching Marianne marry the Colonel—a nod to his comment in the book’s Cleveland confession that he had been watching Marianne at a distance in London perhaps—leaves us feeling his loss.

Colonel Brandon is perhaps the most rounded out of the male leads in the book (he is on the page a little more than the others), and so required the least reworking from Thompson—I mean, hire Alan Rickman to play him and surely your work is pretty much done! Notably more time is devoted towards the end of the film to show Marianne slowly reciprocating the love of the long-smitten Brandon. Writing Brandon his own manly rescue of a soggy Marianne certainly provides a wonderful cinematic parallel to Willoughby’s earlier heroics, although reading Rickman’s relevant diary entry somewhat un-romanticises both scenes!

3 June

The rain pours down — perfect for the shots which remain.

Greg and I carry Kate in turn across the sodden lawn. A piece of green string is stretched to guide our progress.

Having the two diaries to hand also gave me more of an insight into the adaptations made to the script itself through the filming and editing process. Included in Emma Thompson’s book is the shooting script (I assume this is the one they turn up with on the first day of filming), which means that reading along while watching the film I could clearly see what had been cut out along the way.

What is not included again shapes the way the final story is told, and while as we’ve discussed above the male leads were given more depth by Thompson, not all their scenes made the final cut. They had filmed a scene where Brandon visits his ward to flesh out that subplot, and Alan Rickman, who is also frank in his diary on the frustrations he found working with Ang Lee, was clearly disappointed with the excisions made to Brandon’s screen story:

22 January 1996

Watch S&S in growing dismay. It has been cut to focus only on the women’s journey — the men are mindless. Sad — we should care who they are marrying.

23 January

Still brooding, of course. There is a definite sense with S&S that all the corners have been knocked off — no eccentricities, no focus on what is happening to (particularly) Brandon. We are holding the plot together.

Thankfully by the time it came to watching the premiere, Rickman had softened a little, and enjoying an evening with “old friends in new frocks” his final verdict was:

“Terrible sound but cuts apart it’s a beautiful piece of work.”

One particular cut, filmed and later deleted, perhaps goes a little way to negate Paula Byrne’s suggestion that the film is too idealistically romantic. Removing this scene shows that Lee was keen not to veer into the territory of the overly sentimental. And as lovely as it is to have a bit more screen time for a finally united Edward and Elinor, I can see that there is much more impact in leaving us basking in the pay-off of that incredible declaration scene.

Emma Thompson describes filming the scene in her inimitable style:

MONDAY 1 MAY: Everyone hauling their way through the day. Kissing Hugh was very lovely. Glad I invented it. Can’t rely on Austen for a snog, that’s for sure. We shoot the scene on a hump-backed bridge. Two swans float into shot as if on cue. Everyone coos.

‘Get rid of them,’ says Ang. ‘Too romantic.’

Finally, the stunning look of the film cannot go unmentioned. The sweeping shots of the misty Devon countryside accompanied by the beautiful Patrick Doyle soundtrack—oh my heart. In the Jane Austen House lecture mentioned above, Professor Kathryn Sutherland makes the beautiful comment that “heritage filmmaking turns text into artwork” and there is arguably no greater example of this than Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility.

Within the discussion, screenwriter Laura Wade talks about how well the visual language of the film shows us the change in circumstances of the Dashwoods. The rooms of Barton Cottage are small and sparsely furnished and often the action taking place within is filmed through the doorway. The clever, moving and funny scene following Willoughby’s sudden departure, where Elinor is viewed from above perching on the stairs drinking a cup of tea tightly surrounded by three closed doors, the sobbing of a family member audible behind each one, conveys so much information without words. Genius.

One of my favourite ways of interconnecting period dramas is matching up the stately homes they are filmed in. I can often be relied upon to correctly identify a frequently used interior or exterior, and Sense and Sensibility introduced me to an all-time favourite, the Double Cube Room at Wilton House in Salisbury.

This particular room (designed by Inigo Jones in the 1650s) is an absolute stunner, with its enormous Van Dyck painting forming a beautiful, impressive and instantly recognisable backdrop.

In Sense and Sensibility, it is used as the London ballroom where Willoughby is found at last and lost forever. The relationship with Austen has continued to blossom over the years and you may also recognise it as an interior of Pemberley from Joe Wright’s 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, and my absolute favourite use of its incredible beauty, as Donwell Abbey in Autumn de Wilde’s aesthetically impeccable 2020 adaptation of Emma.

More recently still, the Double Cube Room has become the home of two favourite Netflix queens, featuring in both The Crown and Bridgerton.

Keep your eyes peeled, who knows where it will turn up next—Netflix’s upcoming Pride and Prejudice adaptation perhaps.

As much as I will argue (to the death, if necessary) that Austen was a prodigious wit, literary groundbreaker, satirical societal commentator and proto feminist, I certainly don’t take the (somewhat blinkered) line that she was not also a romance writer.

She created some of the greatest love stories in literature, still constantly referenced and swooned over and (probably unhelpfully and unwisely) used as relationship benchmarks today.

And through the filming of Sense and Sensibility, Austen indirectly had a hand in one of the loveliest and longest marriages in the British acting world—the utterly off-book match-up of Elinor and Willoughby (Mrs Jennings did not predict that one!), aka Emma Thompson and Greg Wise.

Thompson and her first husband, Kenneth Branagh, divorced in 1995, the year of filming S&S. Although at the time the press statement accompanying the announcement stated conflicting work schedules as the reason behind the separation, it later emerged Branagh had been having an affair (and ET’s more recent comments suggest it wasn’t the only one) with Helena Bonham-Carter.

So that is the backdrop to our heroine’s arrival on set. She is heartbroken (“I spent January in tears and a black dressing gown”) and also overwhelmed with the huge task ahead as both screenwriter and lead actress in making the dream of S&S that she has been working on for years with producer Lindsay Doran finally come alive.

Little did she know that this film would change her life in a completely unexpected way.

Greg Wise, on the other hand, did apparently have an inkling of what was in store, as a so-called ‘witchy friend’ of his predicted he would meet the love of his life on set. His initial assumption was that this would be Kate Winslet and they went on a date to Glastonbury together, but there was nothing more than friendship between them. It was obviously with Emma Thompson that a spark began to grow.

Thompson is noticeably (and perhaps unsurprisingly) silent on this in her Sense and Sensibility diaries—she occasionally refers to herself as lonely, and feeling unattractive and old, and likens Wise’s arrival on set to releasing a colt in the make-up trailer. It seems he proved to be in every way the shot of energy the cast (and ET) needed.

Nothing telling or salacious on the budding romance to be found in Alan Rickman’s diary either, but I love this throwaway line, referring to a reception held for S&S on 30th March 1996:

Emma & Greg brown & happy.

Greg Wise and Emma Thompson married in 2003 and are still together now.

I think Austen would approve.

I fully appreciate that you’ve been reading about the finer details of all things Sense and Sensibility for some time now and are probably ready for a rest (and by all means, go and pop the kettle on before reading on), but I did want to touch upon the 2008 Andrew Davies adaptation for the BBC, providing as it does the opportunity to look at how the same story featuring (largely) the same cast of characters can be told differently.

With the 1995 film adaptation being so widely acclaimed, I’m sure it was a challenge to find a way to make this three-episode TV series stand apart. Andrew Davies took the helm (perhaps still needing to cross S&S off his Austen adaptation bingo card) and shifted the tone from light and lovely to dark and brooding. We have overt seduction, ominously crashing waves, a duel, angsty frustrated woodchopping in a wet shirt (I did mention it was an Andrew Davies adaptation). There is much less warmth throughout—even the mercurial natures of Mrs Jennings and Sir John don’t quite hit the spot.

The most notable difference from both the novel and Emma Thompson screenplay is in the character of Willoughby. Andrew Davies shows us Willoughby as a cad before the opening credits even roll. We see him seducing a young woman (presumably Colonel Brandon’s ward Eliza, but maybe not, maybe anyone), so we’re under no illusion about who he is when he later appears to rescue Marianne.

Willoughby is no longer instantly likeable, we (like Colonel Brandon) do not fall for his charms and worry for Marianne. The inclusion of the scenes where Willoughby takes Marianne unchaperoned to Allenham is a stroke of genius in allowing us to view the story from a different perspective. In both the novel and the film, Mrs Jennings mentions their improper excursion at dinner—we are a step removed. We can gloss over the real danger of what that situation could have entailed and get back to the witty verbal battle between Marianne being romantic and Elinor focusing on propriety.

Davies shows us a calculating, predatory Willoughby, and an incredibly vulnerable Marianne easily placed to be a further conquest. It is in that vital moment that we see Willoughby shift. He looks at her face and sees an innocence that he realises he can’t take away—he feels so loved and it surprises him. It is not a redemptive change, it is not enough. But in terms of the storytelling, we can now believe that he loved her from that point. Davies includes the Cleveland confession scene (this time with Marianne herself overhearing), but his Willoughby is clearly drunk, bitter and angry. His request for forgiveness is unsympathetically delivered and leaves none of us (Elinor and Marianne included) sorry for him.

The casting is for the most part excellent, Elinor and Marianne in particular (Hattie Morahan and Charity Wakefield). Claire Skinner is fantastic, following in Harriet Walter’s imperious and ridiculous Fanny Dashwood footsteps is not an easy ask and she does it well. I really rate Janet McTeer, but while I see she fits with a tonally different S&S, she somehow feels too formidable for Mrs Dashwood.

Another differentiation from the film is the reintroduction of a few key characters—Lady Middleton, Anne Steele, Mrs Ferrars—who didn’t make the cut in 1995 (Lindsay Doran laments their loss in the ‘making of’ documentary). Daisy Haggard is particularly brilliant as Lucy’s older sister, Anne Steele, with her pitch perfect West Country accent, providing comic relief and incessantly obsessing about ‘beaux’ (legend has it Austen confided in her family that “Anne Steele never succeeded in catching the doctor.” She remains eternally on the hunt for beaux!).

There are some visually beautiful moments in this adaptation. While the overall tone is darker and decidedly less golden and bucolic, there are some wonderful moments where the action is stilled almost like a painting. This happens when we are introduced the whole Middleton clan at Barton Park who line up family portrait style, and my particular favourite is a still image of the back of Elinor sitting on her bed in London and holding all her feelings—chef’s kiss.

The final thing about the TV adaptation that I wanted to look at was the elements that seemed to be borrowed from the film rather than coming from the book itself. The scenes at Norland with Margaret and Edward (who Dan Stevens portrays very much in the blinking, awkward Hugh Grant style) seem to follow Thompson’s lead rather than Austen’s. There are countless visual similarities in location and scene layout. And again we see Brandon given the opportunity to rescue the sad and sopping Marianne at Cleveland. This is really interesting, suggesting a blurring of the lines as to which version of the story is being adapted.

So there we are—finally!

It’s been absolutely fascinating to dive so deeply into how the two adaptations of Sense and Sensibility are similar to and different from the book and each other. I love that the closer I’ve looked, the more I appreciate all the various storytelling choices made by Austen and those retelling her work. I’m less sure what Austen would make of Andrew Davies and his wet shirts, but I’m fairly certain that she and Emma Thompson would get on like a house on fire.

However, I’ve spent so long rounding up my thoughts and shaping all my research into a finished newsletter that I appear to have missed the coach to Meryton—I need to find an alternative means of transport and read 16 chapters of Pride and Prejudice by Sunday! Make haste!

Thankfully a would-be Austen heroine is always up for a challenge!

On a related note, readalong readers might enjoy this recent Tom Gauld cartoon from the Guardian on the perils of microdosing Jane Austen in the office.

Wishing you all a wonderful weekend, and thanks, as ever, for reading.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this newsletter you can support my writing in a number of ways—like, comment, share, consider upgrading your subscription or ‘buy me a coffee’. Thank you!

You may also enjoy these related newsletters:

Northanger Abbey: an Austen update

I am officially a sixth of the way through my year of (re)reading Jane Austen [insert small fanfare here].

If you can't beat 'em, grab your reticule, tie on your bonnet, and join 'em

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Jane Austen is currently absolutely everywhere.

That 1901 edition is dreamy. And those endpapers 😍

Sense and Sensibility is maybe my favourite Austen. I love it. Reading it reminds me of how funny Austen was! Like laugh out loud funny. What a great exploration of a great work.