Ali Smith is, in my opinion, one of our greatest living writers. She understands and transmutes creativity in its broadest sense through her books, both through what she writes about and how she writes about it. She draws so much from art. Takes art out of the gallery, brings it to life by bringing it into life.

How to be both, her multi-award-winning 2014 novel, is the book she wrote before taking on the Seasonal Quartet (four books, Autumn through to Summer, with the appendix of Companion Piece added last year). Reading in retrospect, How to be both feels like a limbering up. The theme of art that threads through each of her seasonal books is front and centre here. An artist, a work of art, characters interacting with and affected by that art and artist.

Here the artist in question is Italian Renaissance fresco painter Francesco del Cossa. Next to nothing is known about del Cossa—there are certainly more prominent fresco artists of that time—but the evidence of his existence comes from a letter he wrote to Duke Borso d’Este asking to be paid more than the other painters working on the ‘Hall of the Months’ in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, because his work was better. When Smith saw del Cossa’s restored work in a magazine, particularly the Month of March, she completely agreed, and made a pilgrimage to see it with her own eyes—the inspiration for the book grew from there (there is a wonderful article on this in the Extra credit section, below).

Not satisfied with her usual playfulness with language and style, in How to be both Smith gets experimental with structure. It’s a book of two halves. Dual parts. Both of which are part one. One part is centred around Francesco del Cossa. One part is contemporary, centred around George, a deep and brilliant teenager, mourning the loss of her deep and brilliant mother. George and her mother visit del Cossa’s work in Ferrara before she dies, and George revisits this memory repeatedly.

When How to be both was published, the two parts of the book appeared in a different order in different copies of the book. The way the story unfolds for you is dependent on which version you have in your hands. The copy I have has the modern story first and the historical one second. That made sense to me. I tried to imagine how reading the other way round would feel—but with the information already in my head one way, I can never really know. (Side note: this reminded me of watching the National Theatre Live adaptation of Frankenstein back in 2011. Jonny Lee Miller and Benedict Cumberbatch alternated playing Victor Frankenstein and the Creature. The night I saw it Cumberbatch was the doctor and Miller his creation, and for me that will always be the ‘right’ way round.)

Interviewed for the Great Women Artist’s podcast (linked below in the Extra credit section), Smith explains that it was reading about the discovery and restoration of Italian frescoes that inspired this structural experiment. The notion of layers, of us seeing things only on a surface layer, not fully knowing what has happened before and lies beneath the layer we are witness to. The underlayer informs our understanding of the surface layer, even though we may not be aware of this. The untold story informing the story.

An intriguing untold story that Smith explores in the book is the possibility that del Cossa was a woman disguising herself as male in order to be able to work. It’s fascinating to hear her talking about her reasons behind this train of thought in the podcast episode, and I really enjoyed this part of the historical storyline.

Smith is an amazing writer we are incredibly lucky to have. As I researched through articles and reviews of her work, there are a collection of words frequently applied to her writing—daring, radical, clever, groundbreaking, experimental. All true. But I think descriptors like these can put people off reading her.

The duality of Smith’s writing is that it is daring, radical, clever, groundbreaking and experimental, and it’s also wonderful to read. You don’t need to understand and absorb every stream of consciousness passage and that doesn’t detract from the story she tells. My favourite word to describe Smith’s style is ‘playful’. She wears her incredible intelligence very lightly and weaves it through her work in a way that shows the fun to be had in being brave enough to let your creativity run truly free. Her work might inspire you to disappear off and learn more about a painting, photograph, artist or writer she mentions. Or it might just leave you feeling vaguely better somehow—expanded. Knowing that there are connections to be made everywhere. Humming the Pet Shop Boys under your breath.

I seem to be very much drawn to art at the moment. Perhaps better put, and as always seems to be the way with these things, suddenly art is drawing itself to me. Everywhere I look there’s an art connection—books, articles, documentaries, films. How to be both could quite happily have led me off on any number of arty interconnections. Ali Smith loves playing around with these herself, so helpfully leaves lots of strings to pull at.

When I was reading How to be both a few weeks ago, I was scrolling through headlines on the Guardian homepage and spotted a fascinating story about a man in York (my local city), whose kitchen fitters discovered 400-year-old paintings on the walls of his flat (link to full story in the Extra credit section below). Decision made. I’m diving into frescoes in fiction—the writing’s on the paintings on the wall.

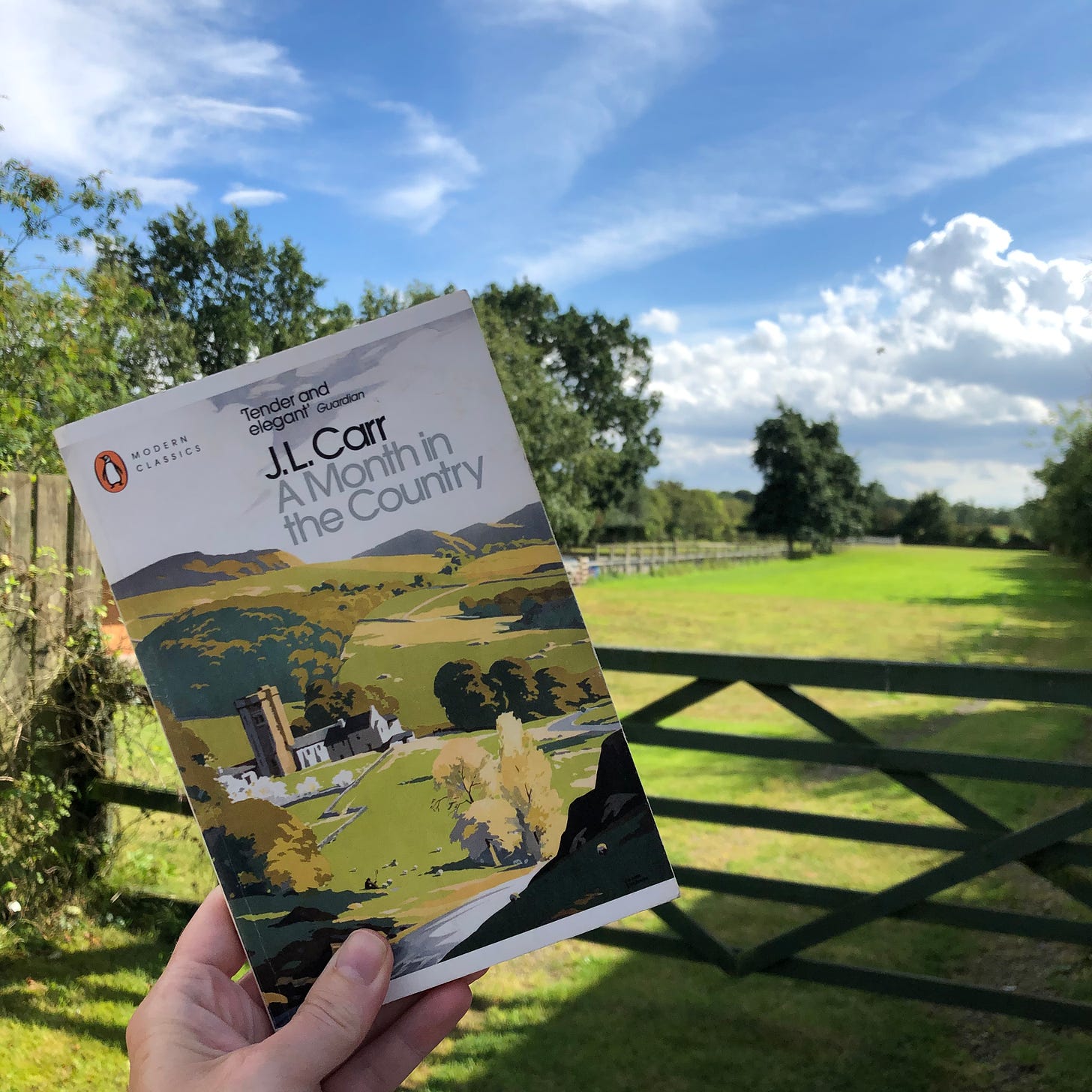

When the connection for this week’s deep-dive made itself clear to me, the first book I thought of was one of my all-time favourites, JL Carr’s quietly beautiful A Month in the Country.

This short novel tells the story of Tom Birkin, a man (like so many) utterly broken by the horrors he witnessed in the First World War. He is transported from London to Oxgodby, a small village outside York (another reason to love it) on the bequest of a rich old lady, and instructed to search for an ancient painting hidden under years of whitewash on the church wall. As he gradually uncovers and restores the work he finds his way back to himself, nurtured by the sense of community and the gentle simplicity of country ways of life so in tune with nature.

The restoration of the fourteenth-century fresco both reflects and enables Birkin’s healing process. The work is slow, deliberate and involving. Painstakingly day by day he uncovers what he believes to be a medieval masterpiece depicting the Last Judgment.

So there I was, on that memorable day, knowing that I had a masterpiece on my hands but scarcely prepared to admit it, like a greedy child hoards the best chocolates in the box. Each day I used to avoid taking in the whole by giving exaggerated attention to the particular. Then, in the early evening, when the westering sun shone in past my baluster to briefly light the wall, I would step back, still purposefully not letting my eyes focus on it. Then I looked.

He pieces together the painting, the story of the artist behind it. He pieces together himself.

I’m always staggered to remember that this was written in 1980; it has such a strong sense of its time. I highly recommend it (read it at the height of summer if you can) and the wonderful 1987 film adaptation starring a very young Colin Firth and Kenneth Brannagh. (Sound the interconnection klaxon: I mentioned Colin Firth in my Mothering Sunday deep-dive newsletter as in the film adaptation he beautifully portrayed a father broken by the loss of his sons in the First World War. Here, Firth’s character Tom suffers from his first-hand experience of the horrors of the Great War.)

The second book that made me think of frescoes was The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje.

Though I can’t even remember the last time I saw the film, this beautiful scene from Anthony Minghella’s Oscar-sweeping 1996 adaptation is still firmly implanted in my mind.

I plucked my aged copy of the book from the shelf and began to try and find the corresponding section. Suddenly it was two days later and I’d reread the whole thing.

I’d forgotten how absolutely stunning this book is. So beautifully written. Again we have people scarred by war, mentally, physically, both. Four misfit characters living out the final days of the Second World War in a bombed-out Italian villa. Kip, the young sapper who stumbles on the group and stays a while, spends his days dealing with the terrifying number of bombs and mines left by the Germans as they retreated. To juxtapose the horror, the pervading sense of death, there is beauty everywhere—the Tuscan backdrop, the villa gardens, the cypress trees, and the art. The villa and particularly the English patient’s room are replete with wall paintings. There is comfort for this suffering man beneath the beautiful, something Kip also seeks out as he travels, sleeping in churches at the feet of painted saints.

The gorgeous scene from the film doesn’t actually happen quite like this in the book. Kip actually shows a minor character, an unnamed medievalist professor, the church frescoes before he arrives at the villa and meets Hana, her patient and Caravaggio. It’s understandable why this was adapted in the film to be part of Kip and Hana’s love story—sharing this moment, the beauty from so long ago providing such a moment of joy and release from the horror of the present, it’s absolutely magical.

Extra credit:

The news story that influenced this week’s choice of interconnection: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/mar/19/kitchen-renovation-reveals-400-year-old-friezes-in-york-flat

Note to self: if you want to get noticed by the Booker Prize judges, write about frescoes. All three books were shortlisted (A Month in the Country in 1980, How to be both in 2014), with The English Patient going on to scoop the prize in 1992, and then the Golden Booker in 2018.

This is the brilliant episode of Katy Hessel’s Great Women Artists podcast that features Ali Smith discussing the artists that appear in her writing. The focus is predominantly on the Seasonal Quartet, but she starts by discussing How to be both, fresco and Francesco del Cossa. Two fascinating women in conversation (chef’s kiss).

Here is a video showing the Francesco del Cossa Month of March fresco (commentary is in Italian, but it at least provides an opportunity to see the work in situ):

This is the brilliant Observer article referred to above written by Ali Smith about her discovery of and visit to del Cossa’s work: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/aug/24/ali-smith-the-finest-man-who-ever-lived-palazzo-schifanoia-how-to-be-both

This is an interesting review of How to be both that focuses on the frescoes and history behind Smith’s book: https://www.bookbrowse.com/mag/btb/index.cfm/book_number/3154/how-to-be-both

As alluded to in the final line of my How to be both review above, Smith interconnects the Pet Shop Boys via the discovery that the ‘Palazzo Schifanoia’ translates as ‘the palace of not being bored’. Cue an argument between George and her Mum about the lyrics of Being Boring. This sent me straight off down a rabbit hole. I’d remembered the song movingly referenced friends Tennant had lost to AIDS, but that a quotation from Zelda Fitzgerald (someone’s wife/a famous writer/in the nineteen twenties)—“she refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring”— was the backbone of the lyrics was a completely new discovery. Enjoy!

Hello Claire, thank you for such a wonderful piece. I love your writing and I am also a huge Ali Smith fan - you have nailed exactly what I most admire - she is beyond clever yet “wears it so lightly”. So much to explore from your essay above and I can’t wait to follow all the links. Much like when reading the seasonal quartet - I would have 20 tabs open to research after even just a chapter sometimes! The frescoes on the walls in Europe, especially Italy, were one of the key things that fascinated me as a wide eyed Aussie backpacker in the 90’s. I am equally enthralled these days by modern wall art & murals, graffitied or otherwise. Perhaps these artists are giving us the new style frescoes! In regional Australia they have started commissioning artists to paint the giant silos that dot the landscape and they are also beautiful. Anyhow, I digress. Thanks again for a lovely and interesting read.

Gosh Claire, you have put so much work into this piece. It wouldn't be out of place in any of the broadsheets.. 🌻🌺 And yes, Being Boring is such a great song, the album Yes is one of my favourites (Being Boring isn't on it though) but the wonderful Beautiful People is!